This is the last of three posts in a series looking at rehabilitation as an aim of punishment. Click the links to access the first and second posts in the series.

How relevant is Struggle for Justice today?

In England and Wales today, our criminal justice system (measured purely on the basis of imprisonment rates and sentence length) is among the most punitive in Europe, though still much less punitive than the contemporary USA. There are an unusually high number of lifers serving severe and indefinite sentences. In spite of this, attempts at rehabilitation are not dead. There is a substantial literature on ‘what works‘ in rehabilitation, standing on a firmer evidential base than in the past. Risk assessment is more systematic and transparent than when it was principally a matter of official discretion, and discretion itself has been checked by the publication of more transparent policies, and by more clearly stated rights for prisoners. These developments kick away some aspects of the case against rehabilitation that the authors of Struggle for Justice put forward.

On the other hand, Struggle for Justice’s core argument (i.e. rehabilitative power can become unaccountable, and increase the severity of punishment) is not entirely irrelevant today. Knowledge of ‘what works’ remains imperfect, and what knowledge there is doesn’t always agree about who is doing the ‘work’ in rehabilitation. Risk assessment and sentence planning can lack transparency for those being punished (who are most affected), with the result that some find it difficult to navigate what is required of them and are punished for longer as a result. Rehabilitative provision has been damaged by austerity, and is directed towards those held to pose the greatest ‘risk’ to others, arguably at the cost of those whose needs are complex but who pose a risk mainly to themselves. Power differentials, particularly in prisons, remain steep. Rehabilitation, in short, can still be framed in a relatively narrow, top-down way, and the help it offers can be diluted by other objectives.

So while times have changed, I think historical texts such as the AFSC report can be instructive: they show how seemingly familiar issues once had very unfamiliar features, and force us to think about change alongside continuity in this way. What we take for granted is shown to be contingent, and we are jolted out of our assumptions. This can help us to notice aspects of contemporary reality which we might otherwise miss.

Are lifers ‘rehabilitated’ by lengthy imprisonment?

Recent research has demonstrated that many long-term prisoners manage to glean something positive and valuable from the sentence, despite finding the experience immensely painful and troubling, particularly at the start. They are very unlikely, compared to other released prisoners, to commit further offences in future. If this outcome is our measure of success, then it’s tempting to conclude that long-term imprisonment is ‘working’: the ends justify the means, and prisoners are ‘being rehabilitated’.

Struggle for Justice suggests that this conclusion might be a mistake. It does so by highlighting that ‘punitive’ and ‘rehabilitative’ are not opposites. Creditable intentions do not automatically excuse discreditable outcomes. Rehabilitative punishment is still punishment: still coercive, still damaging, still capable of producing side effects.

A more useful distinction to make is between ‘rehabilitation’ and ‘retribution’. This draws attention not to whether coercive power is in itself the problem, but to what it is being used for. If it aims at ‘retribution’, it seeks simply to exact a price for past wrongdoing. As the Quaker writer John Lampen suggests, we might think of revenge as an ugly motive. But it is a simpler goal to define and evaluate than that of ‘changing’ someone.

It’s therefore also simpler to hold retributive power accountable. Rehabilitative power, by contrast, can more easily grow out of check. If the excesses of retribution are ugly but obvious, those of rehabilitation can be insidious and disguised: a dangerous road paved with good intentions.

Does life imprisonment ‘work’?

Second, we should be wary of justifying the use of coercive power to rehabilitate people simply on the basis that it seems to ‘work’. Most of us can imagine situations in which the ends don’t justify the means. For example, one way to make future offending less likely would be to physically mutilate, maim or kill the prisoner. Many people (and, I’d hazard a guess, all Quakers) would find such practices unacceptable, indicating that moral judgments play some part. If it was simply a question of ‘what works’, then such judgments would play no part.

More subtly, there are many ways in which prisoners might not just be ‘being rehabilitated’ — i.e. acted on by state power — but instead are ‘rehabilitating themselves’. Generally, limited resources are rationed, and ‘neo-paternalist‘ forms of rehabilitation offered as a priority to prisoners who are classified as posing the highest risk. Such interventions (typically lasting months) typically form a tiny part of a life sentence (typically lasting decades). They can be resented by prisoners who experience them as condescending and manipulative, and engage guardedly or cynically, if at all. This was evident when one man I interviewed in 2017 suggested that the ‘voluntary’ language of rehabilitation programming failed to mask the coercion that underlay all aspects of his indeterminate sentence:

They say, “oh, we think you might benefit from doing PIPE.” Really, what they’re saying is, “we want you to do PIPE. You’ve got to do PIPE […] because you won’t be going to C-cat [i.e. a lower-security prison] otherwise” […] It’s just Catch-22. Basically, I’ve got to do it.

‘Luke’ (not his real name)

What really motivated him, he said, was getting out of prison so that he could provide for his family and be a ‘proper’ dad to his daughter. Currently it is hard to imagine the state intervening to prescribe parenthood or employment for prisoners, even if these are proven to be the most effective ‘treatments’ for their offending. Would fatherhood have given him the motivation to make a better life? If so, are rehabilitative interventions an honest attempt to seek his ‘benefit’, or are they (as he suggests) simply a sweetener for medicine he has to take anyway?

Accounting for the cost of life imprisonment

What we are left with is the finding that lifers and long-termers tend not to reoffend, and that the processes underlying this are poorly understood. I think this means we can’t properly evaluate long-term imprisonment without going inside prisons and taking quite a micro-level perspective on how power is being used, and how it feels to prisoners themselves to be subjected to it.

This means paying attention to their individual experiences, and not only aggregate measures such as reoffending rates. How does it feel to serve a long prison sentence? Is punishment more legitimate or painful to some people than others? How difficult is it to demonstrate ‘change’ in terms that are intelligible to the officials responsible for paroling them? Is it more difficult for some people than for others? Do some find it easier to benefit from rehabilitative programmes, education or work? I think these are questions worth asking.

Questioning rehabilitation

If we still tend to instinctively embrace rehabilitative aims for punishment, then I think Struggle for Justice suggests that we need to ask the following questions, as a starting point:

- in what circumstances are we entitled to dictate to strangers the terms on which they ought to live their lives?

- when (if ever) is it justifiable to hurt people retributively?

- does the claim that we are actually helping those we’re punishing actually help us to duck responsibility for hurting them?

These questions matter, because what is done in our prisons is done in the name of society, and on our behalf.

I’d love to know readers’ thoughts on the report, and the account I’ve given of its arguments.

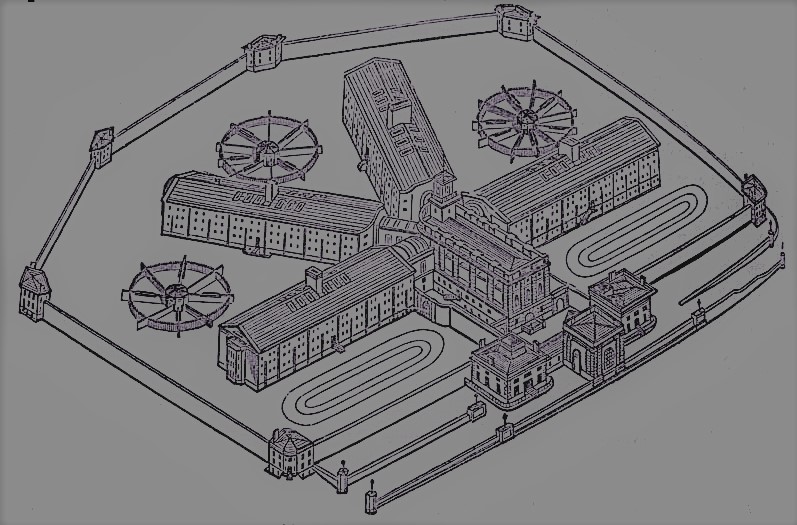

Image: ‘Pentonville Isometric’. Credit: Joshua Jebb or employee via Wikimedia Commons.

References

[zotpress items=”{5344545:CKYAS5PH}” style=”asa”]

Subscribe by email

Use the form below if you’d like to sign up for email updates when I post to this blog.

[rainmaker_form id=”309″]

Leave a comment