This is the first of a series of three posts. It’s been prompted by reading Struggle for Justice, a report published by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC – a Quaker body) in the 1970s. Published at time when the accepted wisdom of the post-war period — which favoured rehabilitation as the proper aim for punishment — was coming under sustained challenge, the report makes a powerful case against rehabilitative theories of punishment.

This might seem surprising today, in the context of a criminal justice system that is often perceived as excessively punitive. In the last several years, for example, successive governments in England and Wales have promised a ‘rehabilitation revolution’ as a means of emptying out prisons. Regardless of whether this has been a success, the language is significant: ‘rehabilitation’ has a certain appeal, holding out the prospect of turning crime, a social ill, into better outcomes in the future. But the AFSC report sounds a note of caution about such language, for reasons that I think are of lasting interest.

Quaker reformers and the aims of punishment

Why is this important? I am a Quaker, and Quakers in Britain are part-funding my research, so this is a matter of personal as well as academic interest. Quaker values are strongly egalitarian, and are often associated with a progressive, reformist, and occasionally a radical political agenda. Quaker reform efforts in criminal justice (especially prisons) have a long history, going back right to the very start of the Quaker movement.

Quaker reform agendas have often grown out of the concern for what individual Quakers understood to be the welfare or betterment of prisoners and others subject to state punishment. It’s fair to note (albeit with the benefit of hindsight) that these agendas have had mixed degrees of success, with some turning out unworkable, and others having unforeseen consequences.

For example, Quakers in the US played their part in the birth of the modern prison as an institution. This invented a system of silence and isolation which was never fully realised, but which is the ancestor of today’s extended solitary confinement, now commonly held not to be reformative but harmful and cruel. One can debate the extent to which the Quakers were instrumental to the creation of the ‘silent system’, but the point here is that yesterday’s penal reforms can become today’s penal problems.

Struggle for Justice appears very aware of this danger. This may in part be a consequence of its authorship. Among its authors, the name John Irwin grabbed my attention. He’s a major figure in prison sociology, and his last book, Lifers, published nearly 40 years later, has influenced recent studies including this one. Crucially, Irwin knew his field from personal experience, having served time in prison as a young man. I wonder how far his lived experience of the excesses of rehabilitation may have shaped the report’s cautious, minimal and sceptical approach to rehabilitative power.

How does Struggle for Justice make its case?

The AFSC report opens with a chapter setting out how the aims of punishment had changed since the early 19th century:

During the last century the professed aims of criminal justice have changed from retribution to rehabilitation and preventive imprisonment. The proper objectives, we have been told repeatedly, are the protection of society from crime and the treatment of the offender, not the exaction of revenge and the criminal’s punishment. [The] words “retribution,” “revenge,” and “punishment” are often used interchangeably, as if there were no significant differences of meaning among them. The resulting confusion is the source of many problems. Retribution and revenge necessarily imply punishment, but it does not follow that punishment is eliminated under rehabilitative regimes.

Struggle for Justice, p.20

For some decades before this, US prisons had officially embraced explicitly rehabilitative aims (although without always realising them). Imprisonment was often described as a form of ‘treatment’, which (in theory) would return the criminal to a ‘normal’, compliant relationship with the law. Punishment, in this account, was the exercise of coercive state power in the interests of the punished.

The authors argued that this simply masked a far uglier reality:

If […] in some circumstances we might employ coercion against an individual to achieve some compelling social goal, it […] obscures the moral nature of our act to pretend that we are not employing punishment […] There is an easy test that can be applied to any purported abolition of punishment or imprisonment. Is the proposed alternative program voluntary? Can the subject take it or leave it? If he takes it, can he leave it any time he wants? If the answer to any of these questions is “no”, then the wolf is still under the sheepskin.

Struggle for Justice, p.23

They took this argument further: even if punishment was guaranteed to benefit the subject, this should play no part in deciding whether to impose it. They offered three reasons for this view:

[T]he paternalism implicit in A’s assumption that he knows better than B what is for B’s benefit is treacherous under any circumstances and becomes an intolerable form of colonialism when invoked by middle-class whites to run the lives of blacks, Chicanos, Indians, and the poor. [T]he natural progress of any program of coercion is one of escalation [so that] the more it is relied upon, the easier it will be to employ it as an evasion of difficult problems and the larger the dosage that will have to be applied […] [And] the availability of coercive solutions to a problem reduces the likelihood of trying more creative but more difficult […] voluntary alternatives […] we think it imperative to regard punishment not as a potential benefit to the subject but invariably as a detriment imposed out of social necessity.

Struggle for Justice, p.25

When is rehabilitation illegitimate?

The first of these three reasons is a principled objection based on what the authors see as the proper relationship between the state and its citizens. The second and third are practical warnings about the dangers of over-reliance on coercion; the third in particular suggests that individuals possess the right to exercise choice over the conditions of their own lives.

Taken together, these are not far distant from the idea, highly influential in today’s progressive/identity politics, that people’s lived experience is authoritative when it comes to the conditions of their own lives. Others might hold them responsible for their actions, but can’t seek negate their experiences or compel them to change their values.

This insight runs through the report itself. For the authors of Struggle for Justice, punishment used coercively to impose ‘help’ on people that they would not otherwise have chosen immediately runs into moral difficulties, and efforts at penal ‘reform’ do not excuse the coercive nature of the institution:

As experienced by the prisoner, imprisonment with treatment is identical with traditional imprisonment in most significant aspects […] The reformist’s range of vision excludes the reality of the view point of the offender […] to the reformist, the only relevant criterion is the purity of the motives of society and its judges and jailers […] We submit that the basic evils of imprisonment are that it denies autonomy, degrades dignity, impairs or destroys self-reliance, inculcates authoritarian values, minimizes the likelihood of beneficial interaction with one’s peers, fractures family ties, destroys the family’s economic stability, and prejudices the prisoner’s future prospects for any improvement in his economic and social status. It does all these things whether or not the buildings are antiseptic or dirty, the aroma that of fresh bread or stale urine, the sleeping accommodation a plank or an innerspring mattress, or the interaction of inmates takes place in cells and corridors […] or in the structured setting of [group therapy].

Struggle for Justice, pp.25 and 33, italics added

For this reason, they argued, punishment should only be thought of as a harmful last resort, and never as of potential benefit to the convicted person.

On first glance, this is quite a challenging conclusion to reformers: ruling out any form of positive outcome risks being used in support of ever-harsher versions of punishment. However, the report does not argue for the withdrawal of support from those caught up in the criminal justice system, but rather the separation of support from coercion.

In the next post, I’ll develop that point.

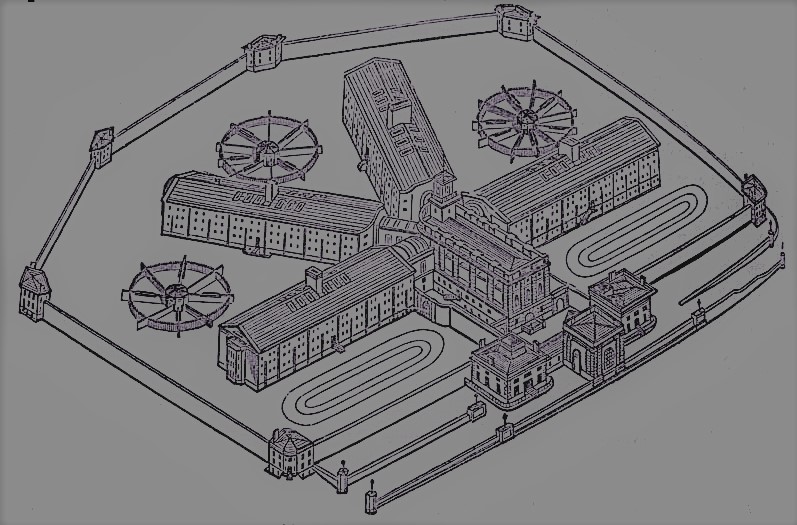

Image: ‘Pentonville Isometric’. Credit: Joshua Jebb or employee via Wikimedia Commons.

References

[zotpress items=”{5344545:BVL74N3Y},{5344545:CKYAS5PH}” style=”asa” sortby=”author”]

Subscribe by email

Use the form below if you’d like to sign up for email updates when I post to this blog.

[rainmaker_form id=”309″]

Leave a comment